By Katrin Kleemann and Nils Theinert

In 1962, a dredge engineer discovered a medieval cog whilst working in the harbor basin in the city of Bremen in northern Germany. Its discovery prompted the foundation of the German Maritime Museum (DSM) in 1971. The museum opened its doors to visitors in 1975. It is the German Maritime Museum’s task to collect, record, research, and present documents and artifacts pertaining to German maritime history. It is the largest museum of its kind in Germany and focuses on the eventful relationship between humans and the sea.

In 1980, the museum took part in the joint research initiative called the “Blue List,” known today as the Leibniz Association. The Leibniz Association is a funding body in Germany for 97 non-university research institutes from many different disciplines ranging from economics to the pharmaceuticals, astronomy, climate impact research, and virology. These 97 institutes also include eight Leibniz research museums, one of which is the German Maritime Museum. The DSM has a significant number of scientific staff who carry out research projects relating to maritime history in the broadest sense. These staff members also curate research-based permanent and special exhibitions, which reach large audiences and are key to the process of knowledge transfer. The exhibitions showcase how science works as a process.

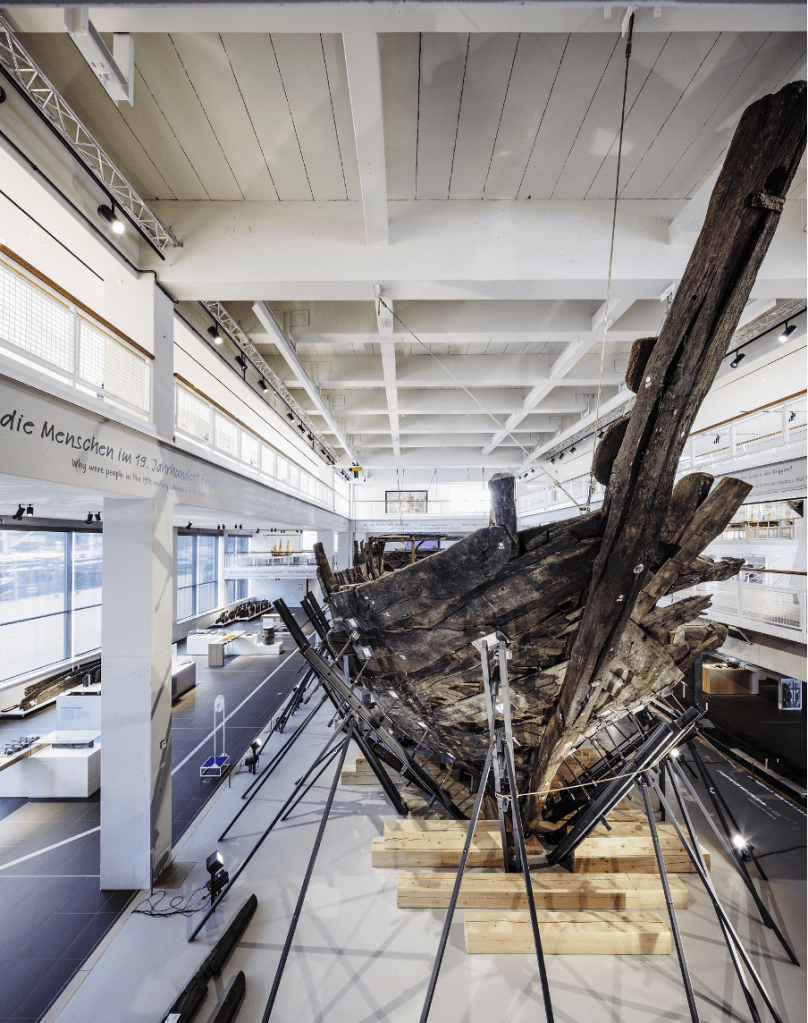

In 2000, the museum presented a Hanseatic cog from the fourteenth century to the public. This happened after a lengthy conservation process, where the vessel was stored in a large preservative-filled basin. During that time, nearly four decades, research at the DSM focussed mainly on the natural sciences, with much focus on the technical aspects of conserving large waterlogged finds. From 2000 onwards, the focus of the research shifted towards the history of science. In 2013, the German Maritime Museum embarked on a new course and embraced “Humankind and the Sea” as a research and exhibition program. A new permanent exhibition, “Schiffswelten – Der Ozean und wir” (World of Ships – Ocean and Us) will open in the summer of 2024.

The museum also has a research library with fabulously helpful staff; a fantastic resource if you need to research anything related to German maritime history. There is an alphabetical catalog online, which works just like any regular library catalog, as well as a systematic catalog. On the library website, you can also find a 25-page list of keywords (in German). Visits to the library can be arranged by getting in touch with the staff.

After the destruction of the Museum für Meereskunde (Museum for Oceanography) in Berlin towards the end of the Second World War, there was no museum or research institute which possessed a centrally curated archive and library about ocean- and seafaring-related topics in Germany. Therefore, right after its founding in 1971, the DSM began to fill this void.

Today, the DSM library houses over 100,000 books and 300 periodicals, covering a wide range of maritime topics—from the history of seafaring to the economic, military, and colonial use of the ocean and its depths. Effectively, the library has become an archive itself. Apart from its many scientific titles, it also acquired a huge amount of popular literature, making it a rich reservoir for the scholar whose research focuses on the changing discourses and cultural histories of ships, oceans, and Germany’s maritime entanglements. It also acquired several extensive privately owned book collections. Among them was the library of Dr. Jürgen Meyer about the history of sailing ships and the collection of Arnold Kludas, the first archivist of the DSM, which largely focused on German passenger ships.

Particularly noteworthy for historians of oceanography, ocean exploration, diving technologies, and their popular representations is the so-called “Documenta Maritima Heberlein.” The lawyer Dr. Herman Heberlein was a Swiss diving enthusiast who represented Switzerland in meetings concerning oceanographic questions at international congresses and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission meetings of UNESCO. He collected a large library that mainly focused on books about underwater photography and cinematography, oceanography, diving technologies, (auto-) biographies of ocean researchers and explorers, underwater archaeology, geography, and nautical topics. It also features rare conference papers and periodicals. The collection was first owned by the Lucerne Nature Museum before it was given to the DSM in 1989. In a three-year project, the DSM librarian Jutta May combined this collection with related titles already in possession of the DSM, creating the most extensive collection of books about diving and oceanography that can be found in Germany. She published a two-volume catalog in 1996 that lists 4302 books and other texts as well as over 1000 periodicals and newspaper articles—dating from the late nineteenth century to the early 1980s; most of them are in German or English. The Documenta Maritima Heberlein offers a comprehensive reservoir of source material about a topic that has yet to receive the scholarly attention it deserves, particularly in the case of scientific diving and its related technologies, and popular representations of the ocean depths.

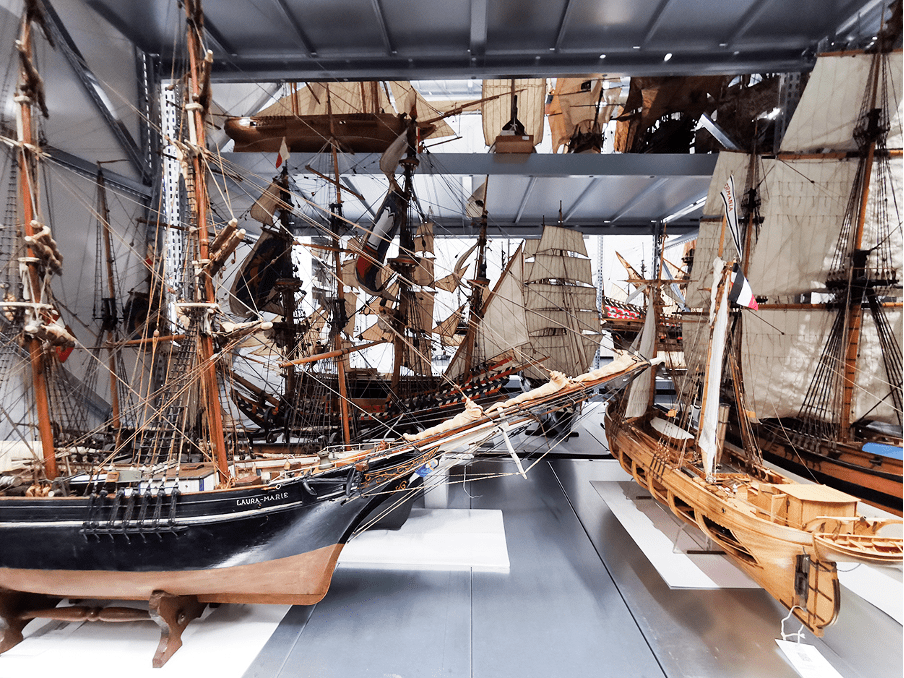

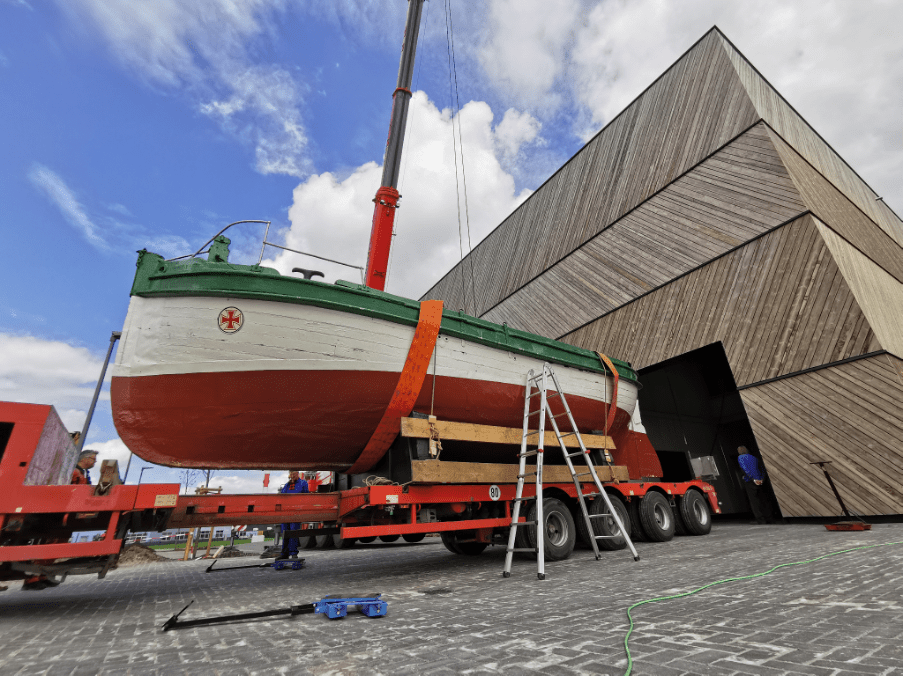

In addition to the library, the DSM’s collections contain approximately 60,000 objects and 380,000 archival materials, including 542 items held by the library—so-called rare titles, those published before 1800. Many of the collection’s objects are currently being moved to the brand-new research depository (Forschungsdepot), a state-of-the-art storage facility for objects and archival materials in Bremerhaven. It has the capacity to house actual ships, ship models, silverware, signaling weapons, nautical instruments, maps, photographs, glass slides, and posters, to mention but a few. The building also has a study zone, where researchers can work with objects and archival materials after contacting the collections staff. For questions relating to archival holdings and images, you can get in touch with the archivist. The DSM archive and library offer rich possibilities for researchers.

In addition to the physical collections, the DSM continuously works on making its collections available online. For the project DigiPEER, approximately 5000 technical plans of trading vessels and special ships from the nineteenth century to the 1960s have been selected, digitized, and are now available online. More than 1000 portraits from the DSM’s collections have also been digitized and have been made available on Digiporta. Currently, the museum is in the process of creating a digital depository to showcase specific items that are relevant to each staff member’s research.