by Aster Hoving

During my PhD research, I was lucky enough to receive a fellowship from The International Commission of the History of Oceanography (ICHO) for my research stay in Japan in the spring of 2024. My dissertation traces the mediation and extraction of hydrothermal vents, tides, waves, and upwelling across contemporary art practices, climate sciences, and ocean energy companies. Before heading off to Japan, I had completed fieldwork on ocean energy practices in three locations across the North Atlantic, so a Pacific Ocean perspective was long overdue.

In Tokyo, I was hosted by Professor Masami Yuki, who leads the Environmental Humanities Forum at Aoyama Gakuin University (AGU).[1] Having access to this lively local environmental humanities research community was a great help as I navigated fieldwork in a foreign language while also taking language classes. I, for instance, ended up participating in a river walk organized by Professor Kejiro Suga from Meji University in Tokyo. Suga, whose diverse body of work includes scholarship on “invisible waves,” works of poetry including the lines “this ocean has an ocean / give this ocean back to the sea / give this ocean to the sea,” and a Japanese translation of Édouard Glissant, in turn, helped me get in contact with the artist Chikako Yamashiro. I was interested in seeing some of Chikako’s work because her artistic practice rigorously and critically engages with historical and contemporary dynamics in Okinawa, where I had planned fieldwork.

The Okinawa prefecture is a group of islands in the southernmost region of Japan. The main island and its capital Naha are located approximately between the Japanese main island and Taiwan. Okinawa has a long history as the independent Ryukyu Kingdom but was annexed by Japan by the end of the 19th century. By the end of the Second World War, about a third of the population of Okinawa died during devastating on-the-ground fighting between the Japanese and American armies. The population suffered so heavily because the Japanese government would not allow them to flee. After Japan surrendered, Okinawa was occupied by the American military until the 1970s. When Okinawa became a Japanese prefecture again, many of the American military bases remained, and to this day the islands have the highest concentration of foreign military bases compared to any other place in Japan.

Yamashiro’s artistic practice, such as the video artworks OKINAWA TOURIST (2004) and Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat (2009) that are on permanent display at the Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum, unpacks the historical traumas and present-day battles of Okinawans under Japanese and American domination.[2] The video artwork Seaweed Woman (2008) explores Okinawan power dynamics from the perspective of the sea as it is filmed from the perspective of a mythical creature of the sea. Seeing through the eyes of this creature, so to say, the camera dives under the bright blue waters around Okinawa and emerges above the surface, witnessing traces of occupation: barriers that run from the coast out into the sea, vessels with coastal guards approaching, and tourists filling up a local beach.[3]

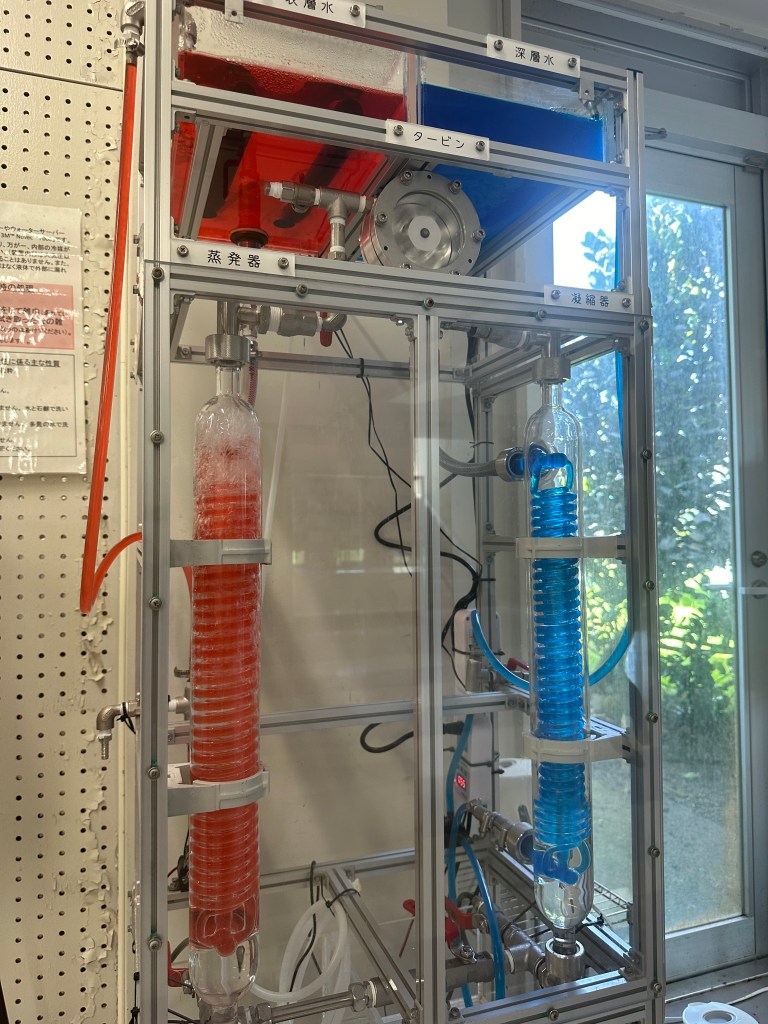

In my research, I explore what dimensions Yamashiro’s creative-critical engagement with the seawaters of Okinawa might add to understanding a contemporary energy experiment on Kume Island, around half an hour’s flight from the main island of Okinawa. The prefectural government initially opened a deep-sea water research center here in 2000. They installed a 2,3 km long pipe leading into the ocean from the beach, reaching 612 meters deep, to transport deep seawater to the shore for research. In 2013, they decided to use water that was left over from research to experiment with a type of energy generation called Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC).

The way this energy generation works is by heating and cooling a fluid with a low boiling point called a refrigerant, creating steam and returning it to a fluid repeatedly to generate electricity. The temperature difference between the upper layer of the ocean and the water in the deep sea is relatively stable on Kume Island, the average temperature of deep-sea water is around 9°C and for surface seawater it hovers around 25°C. These two types of water with different temperatures provide a year-round means to turn a refrigerant into a gas and back to a fluid again. The experiment with OTEC ended in 2019, but the facility is still in place because the water it processes turns out to be energetically useful in another way, too. Besides generating electricity from cold deep-sea water, the temperature of seawater water can also be used to save electricity by using it directly as cooling, especially in aqua- and agriculture. Essentially, the center on Kume Island is now a provider of seawater at six different temperatures, including pre- and post-processing deep sea water and sea surface water. Having continuous access to water at different temperatures means that this water itself is used as (cooling) energy, rather than using electricity to do so.

Being able to see Yamashiro’s artworks in galleries/museums in Tokyo and Naha as well as visiting the OTEC facility on Kume Island has sparked many questions for me to wrestle with in the coming months as I write up my research. On the one hand, using seawater as an energy resource could potentially greatly contribute to the resource independence of Okinawans. On the other hand, large-scale extraction from Okinawa’s oceanic territories could simply intensify the exploitation of the region. After my swim in the warm and salty waters of Okinawa, it is now time to dive further into these complexities of ocean energy cultures and histories.

[1] https://www.agu-environmental-humanities.com/

[2] For a critical account of Okinawan history, see Wendy Matsumura, The Limits of Okinawa:

Japanese Capitalism, Living Labor, and Theorizations of Community, 2015.

[3] For a visual impression of the artwork, see: https://www.mori.art.museum/en/collection/2580/index.html